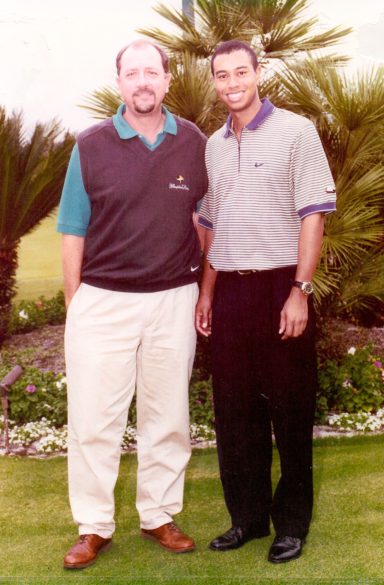

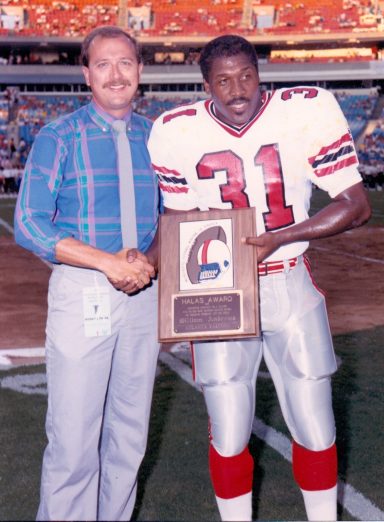

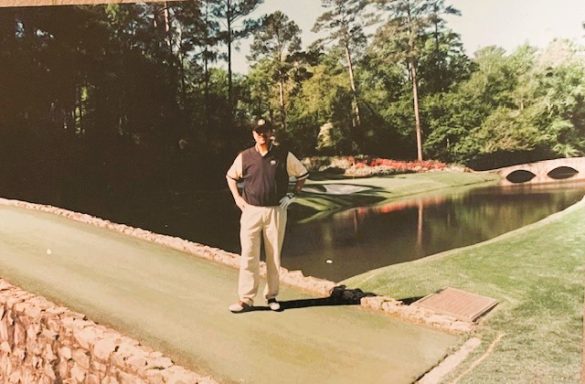

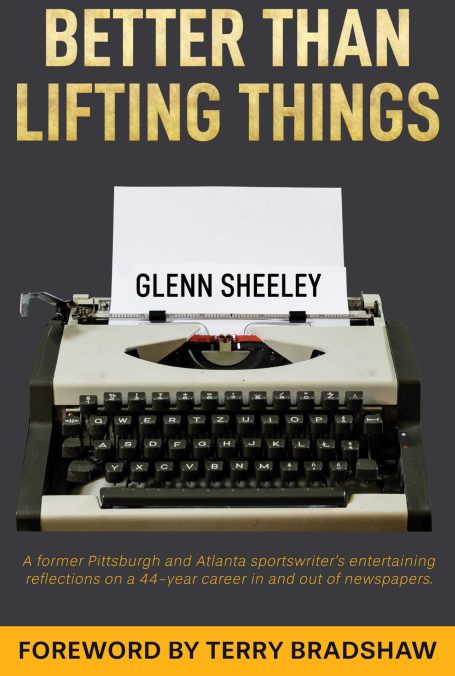

PHOTOS FROM BETTER THAN LIFTING THINGS

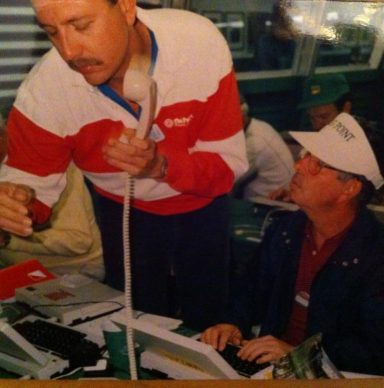

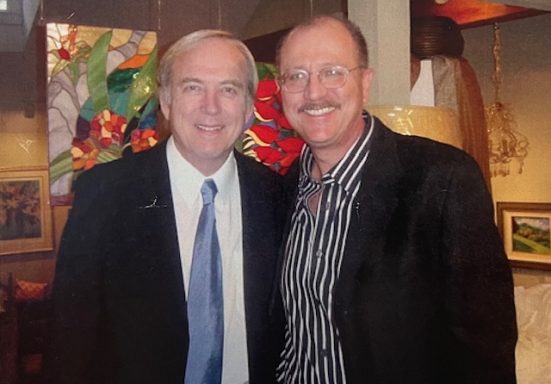

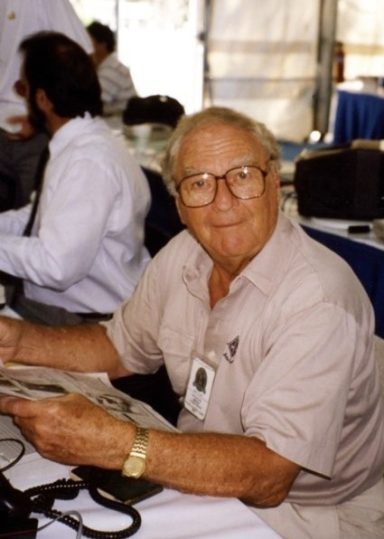

By GLENN SHEELEY

Foreword by Terry Bradshaw

A former Pittsburgh and Atlanta sportswriter's entertaining reflections on a 44-year career in and out of newspapers.

________________

FOREWORD

BY TERRY BRADSHAW

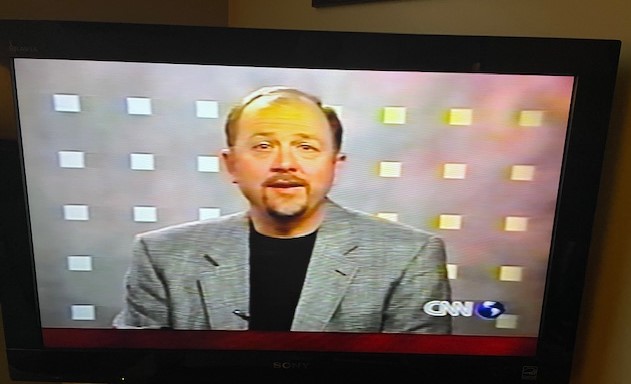

Glenn Sheeley and I were still kids in our 20s when he took over the Steelers beat for the Pittsburgh Press in 1976.

I had seen him around the team a little the year before, when he was helping Phil Musick cover us on the way to our second straight Super Bowl win, but when Glenn showed up at training camp that following summer as the main guy for the Press, I really didn’t know what to expect.

He was another darned Yankee, of course, and I’d heard from Franco (Harris) that he went to Penn State, but I didn’t hold that against him. He wrote some funny stuff, and he seemed like a fair reporter. He wasn’t one of those guys who would just tear somebody apart for no reason. Especially me, and back then it felt like everybody was ripping me for something.

Truth is, Glenn ended up being about the only Pittsburgh writer back then that I really liked and enjoyed. We had a good relationship—or as good as you could have, I guess, with an athlete and a writer—and I remember thinking, I like this guy, I’ll see if maybe I can get him on my side. I guess maybe I was able to because I can’t ever remember being mad at him for anything he wrote.

Sometimes I would even stop by the press room at training camp after evening team meetings and shoot the breeze with him. There was usually nobody else in there, and I was interested in what he was thinking about the team, too. In the process, I tried to give him some inside stuff, usually talking off the record, and Glenn never violated that trust. That meant a lot to me.

After Glenn left Pittsburgh (in 1979) to work in Atlanta (for the Journal-Constitution), we saw each other occasionally around the NFL when I was first working for CBS, and then FOX. And, of course, when I was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1989. But a few years ago, we reconnected again through our mutual friend, John Czarnecki, who worked with me for many years at FOX in Los Angeles after his newspaper career. Now Glenn and I talk every so often on the phone about golf, grandkids, and our health, plus often reminiscing about the many memories we share from Pittsburgh.

I only found out recently that we’re both cancer survivors. Glenn had kidney cancer a long time ago (1998) and I’ve had my issues in recent years. Thank God we’re both around to talk about them.

I was really happy to hear that Glenn had decided to complete this book. I knew he’d been working on it for quite some time and I’m glad it’s finally out there for people to see. When he sent me my chapter a while back, I really enjoyed it and happily replied to him, “You’ve still got it.”

As you might know, Glenn also had a long writing career in golf after leaving the NFL beat, and I’ve always loved golf, too, or at least until my body stopped remembering how to make a decent shoulder turn.

It wasn’t easy covering the Steelers back in the ’70s. You had to be there to really appreciate the craziness. People in hard hats, wearing our jerseys all over town. Black and gold everywhere you looked. The love affair between Pittsburgh and the Steelers was incredible. For the first couple of years after I got there, we were still lousy, and then suddenly we were Super Bowl champions. It seemed like it happened overnight.

I never really thought about it until Glenn asked me to write this foreword, but I guess there was a lot of pressure on him, too, having never covered a pro team before and starting with a two-time Super Bowl champion. Heck, nobody in Pittsburgh wanted to read about anything else, and back then, newspapers were still a big deal. Now it’s all TV, but in the 1970s what was said about you in the paper was just as important as what the TV guys said on Sunday.

In those days, the writers even flew with us on the Steelers’ team charter. I wasn’t crazy about it—I felt that was our place to be, not theirs—but Mr. Rooney wanted all those guys from the smaller papers around Pittsburgh to enjoy the Steelers’ success, too, after putting up with the team in the old days, and they couldn’t have gotten to the road games any other way. Plus, it always gave me a chance to stop by Glenn’s seat while he was trying to write on the plane and give him some grief.

We also shared our mutual frustration with Chuck Noll. Most everybody knows the issues I had with my head coach, but the media guys also had their problems with him. He was often cold to them, too, and considering how friendly everyone else was in the entire organization, Chuck’s aloofness often made it difficult for everyone.

The complete opposite, of course, was Art Rooney, Sr., The Chief. Everybody loved that man, and we cherished the time we were able to spend with him. When I got to Pittsburgh, The Chief was somebody I could always talk to, even in the bad times, and I always appreciated that more than he probably ever knew.

I’m glad I could help out Glenn a little bit by writing this foreword. It’s only fitting since he wrote such a nice review for me on the book jacket of my second book, Looking Deep. Heck, he even liked my 2020 COVID song, “Quarantine Crazy”—which, by the way, should have been a hit—and he owned a copy of my first record album, I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry. I sure hope he didn’t have to pay for it.

Now, here we are, all these years later. Glenn’s retired and I’m still in the media.

But stranger things have happened, I guess. After all, the “Same Old Steelers” really did become four-time Super Bowl champions, didn’t we?

—TERRY BRADSHAW

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.